Frozen in Time

Old photos stare at me, challenging memory.

Yesterday I found an old snapshot of three friends: Kathy, Mary and Sandy. They are holding up a Trivial Pursuit game.

Mary never liked games, Kathy played the lute and gave it up when she met someone who played golf and didn't understand Baroque music, Sandy moved away when she started climbing the corporate ladder. Mary, the Civil War buff, attended enactments in Virginia. In the photo we all didn't know about tomorrow. I helped pack up Sandy's apartment a year later; I cried with Mary when the lump in her breast was malignant and I watched Kathy lose herself. Only the photo remains intact.

Old photo albums stacked one on top of another fill up a shelf of a bookcase. Some contain specific captions: people, place, date and comments. Others rely on memory. I see myself on top of Mt. Katahdin, the wind and cold obvious even in the photo. Gail, my climbing partner, fell on the way down and sprained her ankle. We both ran out of water an hour before we came to the end and then conjured up images of popsicles and Italian frozen ice.

Faith Moosand collects old photo albums. "I rescued them from the nastiness of not being wanted." What happened to the album? Why wasn't it passed down within a family? Perhaps there was no relative. What will happen to all the albums on my shelf? Will someone remove only the photos they want to save and consign the album to the trash or send it out to the marketplace? Faith wrote a book: Futile Gestures: Photo Albums and the Ecology of Memory. She's found scrapbooks of photos where a number of the pages have missing photos or pages are torn out or parts of pages have been cut away. Why? "The destruction,” she says, “may have been carried out by the creator of the album...censorship may have played a role."

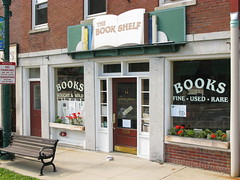

Synchronicity: it's out there in the universe and ready to display itself even if you're not seeking connections. I found a book on the new bookshelf in a local library: a book about the history of the photobooth. I recall taking some photos in a booth in Manhattan.

Two seated friends pull the curtains, smile, and wait for the strip of snaps.

Were we pleased with the results? How did we divide the pictures? What happened to those photos? Have they been collected by a stranger or consigned to some waste basket?

When Joseph Anato invented the photobooth he hoped for success, but did he envision the long lines forming to use the photobooth in Times Square? Soldiers shipping out to World War II took photos to send home. How many soldiers returned? Did they look the same?

It cost .25 in 1925 to obtain a strip of eight different photos. Andy Warhol used the photobooth for the creation of art. In 1986 Bern Boyle created a year long project of taking one photobooth picture a day. He called it his "response to the AIDS epidemic...documenting my life became an obsession."

Sawado Tomoko took one photo a day to "create an army of me". The New York Times reported, "She spent weeks changing her physical appearance and dress to invent a total of four hundred different identities." Then there's Herman Costa who spends afternoons in photobooths creating photocompositions. The Museum of Modern Art owns one of his works.

The digital camera makes it easier to document a life. The Photoblog encourages strangers to post photos, to challenge themselves with a posting everyday for a year, with responding to people all over the world. I posted a photo or more a day for over a year and then posted several times a week. At the end of the year I created DVDs of all the photos and eradicated most of them from my hard drive. Some I saved. There are no albums to look at. What will eventually happen to the DVDs? Will anyone be interested in fifteen photos of brussels sprouts or endless photos of a polypore?

What happens to the photos when scrapbooks disappear? In the 1860s scapebooks stored tintypes. Everything changes.

Yesterday I found an old snapshot of three friends: Kathy, Mary and Sandy. They are holding up a Trivial Pursuit game.

Mary never liked games, Kathy played the lute and gave it up when she met someone who played golf and didn't understand Baroque music, Sandy moved away when she started climbing the corporate ladder. Mary, the Civil War buff, attended enactments in Virginia. In the photo we all didn't know about tomorrow. I helped pack up Sandy's apartment a year later; I cried with Mary when the lump in her breast was malignant and I watched Kathy lose herself. Only the photo remains intact.

Old photo albums stacked one on top of another fill up a shelf of a bookcase. Some contain specific captions: people, place, date and comments. Others rely on memory. I see myself on top of Mt. Katahdin, the wind and cold obvious even in the photo. Gail, my climbing partner, fell on the way down and sprained her ankle. We both ran out of water an hour before we came to the end and then conjured up images of popsicles and Italian frozen ice.

Faith Moosand collects old photo albums. "I rescued them from the nastiness of not being wanted." What happened to the album? Why wasn't it passed down within a family? Perhaps there was no relative. What will happen to all the albums on my shelf? Will someone remove only the photos they want to save and consign the album to the trash or send it out to the marketplace? Faith wrote a book: Futile Gestures: Photo Albums and the Ecology of Memory. She's found scrapbooks of photos where a number of the pages have missing photos or pages are torn out or parts of pages have been cut away. Why? "The destruction,” she says, “may have been carried out by the creator of the album...censorship may have played a role."

Synchronicity: it's out there in the universe and ready to display itself even if you're not seeking connections. I found a book on the new bookshelf in a local library: a book about the history of the photobooth. I recall taking some photos in a booth in Manhattan.

Two seated friends pull the curtains, smile, and wait for the strip of snaps.

Were we pleased with the results? How did we divide the pictures? What happened to those photos? Have they been collected by a stranger or consigned to some waste basket?

When Joseph Anato invented the photobooth he hoped for success, but did he envision the long lines forming to use the photobooth in Times Square? Soldiers shipping out to World War II took photos to send home. How many soldiers returned? Did they look the same?

It cost .25 in 1925 to obtain a strip of eight different photos. Andy Warhol used the photobooth for the creation of art. In 1986 Bern Boyle created a year long project of taking one photobooth picture a day. He called it his "response to the AIDS epidemic...documenting my life became an obsession."

Sawado Tomoko took one photo a day to "create an army of me". The New York Times reported, "She spent weeks changing her physical appearance and dress to invent a total of four hundred different identities." Then there's Herman Costa who spends afternoons in photobooths creating photocompositions. The Museum of Modern Art owns one of his works.

The digital camera makes it easier to document a life. The Photoblog encourages strangers to post photos, to challenge themselves with a posting everyday for a year, with responding to people all over the world. I posted a photo or more a day for over a year and then posted several times a week. At the end of the year I created DVDs of all the photos and eradicated most of them from my hard drive. Some I saved. There are no albums to look at. What will eventually happen to the DVDs? Will anyone be interested in fifteen photos of brussels sprouts or endless photos of a polypore?

What happens to the photos when scrapbooks disappear? In the 1860s scapebooks stored tintypes. Everything changes.